The British Labour Party – born 1900; died 1995 – was a coalition of different tendencies. This is pretty much the standard model of political parties in liberal democracies and these divisions are always a source of internal tension and power struggles, which usually subside if that party comes to power but surface again when in opposition. Generally though, parties that do get into government tend to hold together despite the cracks.

However the Labour Party in the UK was unique in its mixture compared to similar parties elsewhere. Whereas most European social-democratic parties had some kind of marxist basis 1, the Labour Party differed in that the UK already had a strong trade union movement that was indigenous and not much influenced by Marx or marxist thinking. The UK also differed in that in the last half of the 19th century, the Liberal Party had been seen as the defender of working class rights and interests. But by the end of that century the limitations of that relationship were showing more clearly as the mass trade unions, like those of the railway workers and miners, became more powerful than the older ‘craft’ unions. As the pressure for a voice for workers in Parliament increased, those Liberals who favoured ‘social’ liberalism over economic liberalism joined with trade unionists and socialists (social-democrats) to form the Labour Representation Committee. This was the body that grew into the Labour Party.

So, from its inception, the Labour Party was a reformist one and at times has included or worked with groups, like the Independent Labour Party (ILP), the Co-operative Party and the Fabian Society. Its constitution was famously written by two Fabians, Sydney and Beatrice Webb in 1917 and adopted in 1918. The Webbs, like all Fabians, were avowedly reformist, despite their admiration of Lenin and the Russian Revolution, nevertheless they included in that constitution the famous Clause 4:-

“To secure for the workers by hand or by brain the full fruits of their industry and the most equitable distribution thereof that may be possible upon the basis of the common ownership of the means of production, distribution and exchange, and the best obtainable system of popular administration and control of each industry or service.”

This short declaration of intent became the battleground for nearly all the future battles between the left and the right of the Party.

The centre of the dispute was the phrase, ‘common ownership’. For the Webbs and many others it meant nationalisation, for the Co-op Party it meant co-operatives, but for many left socialists it meant full workers’ control. Many within the Party saw nationalised industries and services, preferably under a Labour government, as the same thing as workers’ control.

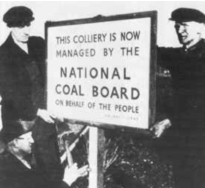

I’ve seen a photo of a group of miners setting up a signboard outside their pit in 1947, which read: “This colliery is now under worker’s control”, whereas the ‘truth’ was shown in the one below.

In fact both groups of men were as deluded as the Russian workers who thought that the ‘dictatorship of the proletariat’ meant they were in control. ‘On behalf of the people’ here meant, as in Russia, on behalf of the government. In other words, state capitalism.

As long as business is good, state capitalism seems to work in the workers’ favour, but they have no say as to the use of profits, the investment of more capital or the development of the industry. The classic case was the GPO, which successive governments milked, whether or not it made money, and hid that extraction from the public when calculating its ‘losses’.

On the other hand, workers didn’t help themselves much either. Trade unions fought for their members interests first and foremost 2 and rarely co-operated. This was reinforced by the ‘closed shop’ which was intended to safeguard unionised workers from having their wages undercut by non-union workers. Instead it led to constant ‘demarcation disputes’ about who had the ‘right’ to a particular job. It also created resentment among those unemployed workers excluded from work. The trade unions in the UK never had ‘too much power’ but they did become inward-looking and self-satisfied. Too often they failed to react to new technologies in time or to keep the public on their side until it was too late.

When the Tories under Margaret Thatcher came to power in 1979, they had their plans to destroy union power in place. Using the right-wing press as their shock troops they pinned the economic downturn, caused by the steep price of oil when OPEC 3 was formed, on Labour and the unions. Cameron and Co have done exactly the same with the collapse of the banks in 2008. In both cases this has left the Labour Party speechless with panic, so it turned on its own left wing for a scapegoat.

If the right wing of the party consists of liberals and reformists who believe in accommodation with capitalism and getting workers the best ‘deal’ they can, the left is, or was, a more varied mix. It included militant trade unionists, left socialists who believed in the gradual achievement of Clause 4’s aims by ‘evolution not revolution’ and, by this time, various Trotskyists. The biggest group of these were organised in Militant Tendency, though there were others, notably the International Marxist Group (IMG, aka the ‘Migs’).

These groups were mostly the product of the near-global revolution of 1968. That year was the high point of radicalism that had spread across the world following WW2, driven by the liberation wars of colonial peoples, civil rights struggles of minorities and a general rejection of the political status quo – especially of the so-called Communist Party, but also the social-democratic parties. But, while the latter were seen as part of the problem, some at least, like the UK Labour Party, could be pushed into making useful legislation. However, with the defeat of those uprisings in France, Czechoslovakia and the USA, militants who still believed in political revolution looked for other tactics. Trotskyists, who saw themselves as the true heirs of Marx, in the UK began a programme of ‘entryism’. This involved joining the Labour Party, not with the intention of taking it over, but pushing a left-wing agenda and ultimately recruiting as many of its disaffected militants as possible before leaving with them and setting up a ‘real’ revolutionary party. Unfortunately their ‘analysis’ of the situation in 1980s Britain failed to take account of the forces against them and the lack of fight amongst the working class. They became the best target the Labour right had had since the Communist Party in the 1930s.

The settling of accounts came in 1986. One bunch of right-wingers had already jumped ship in 1981 and set up the Social Democratic Party, unconscious of the irony that the first with that name was founded by Karl Marx. Then the right sat back and let the triumphalist left write the manifesto for the 1983 General Election. This reasonable, if hopelessly optimistic, wish-list, dubbed by Gerald Kaufman as ‘the longest suicide note in history’, was then blamed for the party’s third defeat in a row. Everyone else knew that had been caused by Thatcher’s ‘victory’ in the Falklands War.

So, at the Labour Party Conference in 1985, Neil Kinnock declared war on Militant Tendency. Those who did not renounce the faith were soon expelled. The right wing of the party had finally won and awarded themselves a red rose to celebrate the fact (thus alienating all their supporters in Yorkshire). Nor was this their only error. Not only did they get rid of those invasive Trots, they also lost most of their young activists who were in touch with the ‘grass roots’ – not perhaps the Labour hard core voters and trade unionists who still had jobs, but all the rest whose lives and livings were being decimated by Thatcherite ‘monetarism’ and the mass exodus of capital and industries to cheaper off-shore havens of exploitation.

The defeat of the Tories in 1997 was misread by the right as a vindication of their policies. They followed up Kinnock’s ‘New Realism’ – neither new nor realistic, just the mantra that they’d never win again without middle-class votes – with New Labour. A wave of, mainly university-bred, MPs and ‘advisors’ took over in the sure belief they could run capitalism better than the Tories. For a while they did.

Sadly, in fact, Labour was already dead. At the party conference in 1995, they had ditched Clause 4 and with it any pretence that they were a party of ‘labour’. They had watched as the Tories wiped out whole industries, sold off nationalised ones, sold off council housing to tenants, sold mental hospitals and school playing fields to ‘developers’, destroyed the National Union of Mineworkers and outlawed any effective industrial action by other unions. When they got back in power under Blair, none of this was reversed. Furthermore they had colluded in the enforcement of the Poll Tax until mass action broke it down. Ignoring the haemorrhage of working class activists and belief, they put their faith in ‘floating voters’ and the residual traditions of sympathy in the once-upon-a-time industrial heartlands.

They’ve lost the plot and don’t know where to look for it. The slaughter of their Scottish MPs in the election of 2015 was not a result of rising nationalism – the referendum made that clear – but a total loss of any trust in the Labour Party to defend them from the Tories’ depredations, whether in power or not. The Labour leadership weren’t even able to defend themselves from the ludicrous lie that they, and not the casino banks, were responsible for the economic collapse since 2008. They weren’t because Gordon Brown had made it clear in 1997 that he would be continuing Tory economic policies. To admit that would be to reveal how far right they’d moved. There’s nothing left to choose between them and the liars and thieves running the country. Small wonder that many working class voters looked to UKIP’s clowns to save them from redundancy and penury.

I see little hope for the future of that corpse being revived. In the last two years there has been a major revival of Labour’s membership under the leadership of Jeremy Corbyn. To the horror of the Labour right wing, the left has returned stronger than ever but they refuse to accept it. They’re totally glued to the idea that a socialist Labour Party in unelectable and are doing everything in their power to stop Corbyn and his supporters in their tracks. So far, apart from saying so out loud in public, they’ve collaborated with zionist activists to accuse of anti-semitism any critics of the Israeli government’s policy of apartheid and ethnic cleansing in the West Bank. They’ve even tried to accuse the Trotskyists of trying to take over the party again, even though they’re shadows of their previous selves. No trick is too dirty to use. Corbyn, meanwhile, continues to try to hold the party together and, outnumbered by his enemies in Parliament rolls over and reluctantly agrees with the right’s policies and lies. Unless he finds his backbone, the Labour Party isn’t just a headless chicken, it’s a gutless one too.

ra 10.5.15, updated 1.5.17

1 Although many European socialist parties still have their roots in marxism, the rise of the Communist Party after the Russian Revolution saw them all rejecting it and any attempts at revolutionary change.

2 This was almost always built into their constitutions, which saw their rôle as solely looking after the interests of their members within the current system and nothing more. So they’ve had no other agenda beyond fighting for more pay, improving conditions of work (rarely) and hanging on to jobs and old practices in the face of changes in their industries and services. The NUM, the union with the best record of defending other workers, especially nurses, was crushed with Labour’s approval. The Tories had managed what Barbara Castle and ‘In Place of Strife’ had failed to do.

3 The Organisation of the Petroleum Exporting Countries, who had organised themselves for the first time to get a fair price, instead of letting the oil companies continue to rip them off.

Disclaimer: the above is a personal and frankly partisan (not party) opinion piece of someone who lived through the second half of the 20th century and been on the fringes of some of the events described. Historians and partisans of other credos will undoubtedly trash it. Good luck with coming up with a better one.